Essay on Investment Theory

The Three Faces of Value

There is no such thing as absolute value in this world. You can only estimate what a thing is worth to you.

The stock market is complex because people that come to trade have radically different expectations with respect to issuers of securities.

Some look to issuers as a source of income, others as a means for personal power, and still others as a playing card to bet on.

The people buying, selling, and holding equities are not entirely sure of their own values and watch one another and are influenced by their respective opinions and actions.

Searchers for truth that develop theories of value also fall into different camps.

The Three Players

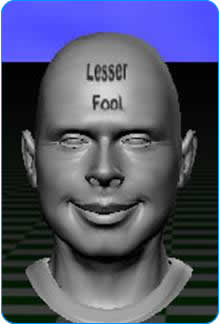

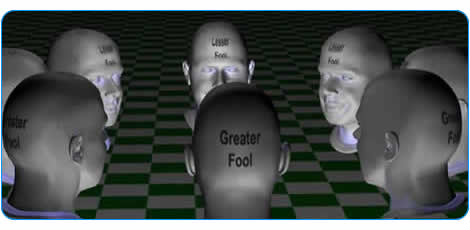

Although the leading view varies from market to market and from time to time, most investors display some combination of three basic personality traits, that we will call Mr. Lesser Fool, Mr. Dividend, and Mr. Control.

Much of investment theory developed by modern economists, is based on the philosophy of Mr. Lesser Fool.

Modern economists often follow the steps of Mr. Lesser Fool.

In contrast, Benjamin Graham, John Burr Williams, and their followers of the Value School favor the views of Mr. Dividend.

Mr. Control, however, still waits for academics to explain and justify his behavior.

For sound commercial reasons, Wall Street loves Mr. Lesser Fool and Mr. Control, but looks upon Mr. Dividend with suspicion and disdain.

These personalities interact.

They have distinct ways of valuing equities and, to a greater or lesser degree, try to convert others to their view.

As a result, the dominant opinion of the investment crowd regarding value changes, as does the nature of the market.

Mr. Lesser Fool

There are some people, who we personify as Mr. Lesser Fool, whose idea of investing is summarized in the saying, 'Buy low, sell high'.

John Maynard Keynes described the thinking of Mr. Lesser Fool in this famous paragraph from 'The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money.'

'The actual, private object of the most skilled investment today is 'to beat the gun', as the Americans so well express it, to outwit the crowd, and to pass the bad, or depreciating, half-crown to the other fellow.

John Maynard Keynes described the thinking of Mr. Lesser Fool in this famous paragraph.

This battle of wits to anticipate the basis of conventional valuation a few months hence, rather than the prospective yield of an investment over a long term of years, does not even require gulls amongst the public to feed the maws of the professional; – it can be played by professionals amongst themselves.

Nor is it necessary that anyone should keep his simple faith in the conventional basis of valuation having any genuine long-term validity.

For it is, so to speak, a game of Snap, of Old Maid, of Musical Chairs – a pastime in which he is victor who says Snap neither too soon nor too late, who passed the Old Maid to his neighbor before the game is over, who secures a chair for himself when the music stops.

These games can be played with zest and enjoyment, though all the players know that it is the Old Maid which is circulating, or that when the music stops some of the players will find themselves unseated.'

Mr. Lesser Fool's idea of an investment plan is to buy at ten dollars in January and sell for fifteen dollars in March.

Mr. Lesser Fool has many reasons to back this strategy, ranging from technical charts and fundamental analysis, to astrological readings and academic papers of great mathematical complexity.

However, his basic philosophy is not to expect anything from the issuer of a stock, but rather from some other investor.

When Mr. Lesser Fool expects profit in the short run, he may concede that he is a speculator, although he would prefer to be called by the more dignified title of trader.

However, when Mr. Lesser Fool hopes to realize capital gains over a long period – say fifteen to twenty years like typical owners of 401(k) funds – he would be offended if anyone called him anything other than a serious investor.

Greater and Lesser Fools

Nevertheless, whether Mr. Lesser Fool plans to cash out in one day or thirty years, he always expects to do so by selling at a profit to Mr. Greater Fool, who may or may not exist.

Mr. Lesser Fool gets high on paper profits.

Mr. Lesser Fool gets high on paper profits and waits with anticipation to cash out to Mr. Greater Fool some sunny day.

It is curious that Mr. Lesser Fool is seen by others as the spitting image of his clone, Mr. Greater Fool.

Therefore, Mr. Lesser Fool is comforted as he looks around the market seeing many Greater Fools, as they are when they look at him.

Mr. Lesser Fool is the spitting image of his clone, Mr. Greater Fool.

Mr. Lesser Fool is the spitting image of his clone, Mr. Greater Fool. Smarter Than The Market

Mr. Lesser Fool also holds to the odd belief that he is smarter than the market, or that, at least, he has an adviser who is smarter.

However, he has a touch of the manic-depressive, and his faith in his ability to predict the market varies from supreme confidence to the pits of self-doubt.

Mr. Lesser Fool outnumbers other kinds of investors in equities.

In the last two generations in much of the world, Mr. Lesser Fool has out-numbered other kinds of investors in equities.

When market prices fall, Mr. Lesser Fool is quick to blame 'lack of investor confidence' by which he means a dearth of Greater Fools.

He calls on the government to do something to restore this esteemed value.

He also assumes that when he has lost money because prices have fallen sharply, that someone must be to blame.

A Believer In The Legend

Mr. Lesser Fool is a devout believer in the Common Stock Legend and holds that diversification and dollar-cost-averaging will assure that he will win in the long-run.

Mr. Lesser Fool, a 'friend of the trend', runs with the pack.

Mr. Lesser Fool runs with the pack.

He is a social being who likes to 'go with the flow'.

He gathers confidence from the adage, 'The trend is your friend'.

He is impressed by the opinion of those claiming to be experts, especially when these opinions coincide with the belief of the crowd.

Mr. Lesser Fool hopes that diversification, index funds, a 'long-term view', and dollar-cost-averaging will overcome a lack of hard research and judgment in selecting stocks.

Mathematics and Value Investors

Mr. Lesser Fool may use John Burr Williams' formula to put a value on stock.

However, by jiggling the estimates for investment discount and dividend growth, any value can be created.

One person can say a stock is worth five dollars, while another says its value is five hundred dollars, while both use the same equation.

Benjamin Graham, the guru of fundamental analysis, had this to say about using mathematics in securities analysis:

The point I want to make here is that there is a special paradox in the relationship between mathematics and investment attitudes on common stocks, which is this:

Mathematics is ordinarily considered as producing precise and dependable results; but in the stock market the more elaborate and abstruse the mathematics the more uncertain and speculative are the conclusions we draw there from.

In forty-four years of Wall Street experience and study I have never seen dependable calculations made about common stock values, or related investment policies that went beyond simple arithmetic or the most elementary algebra.

Whenever calculus is brought in, or higher algebra, you could take it as a warning that the operator was trying to substitute theory for experience, and usually also to give to speculation the deceptive guise of investment.

(The Intelligent Investor, Benjamin Graham, Second Revised Edition, 1959, Harpers & Brothers)

Although Mr. Lesser Fool may occasionally use mathematics to prove that stocks are not over-valued, his real basis for investing is the Common Stock Legend.

His article of faith is simply that a randomly selected, diversified portfolio of stocks will in the long run provide a higher return than any other investment.

He believes that this has always been so and will always be so.

Mr. Lesser Fool believes in selective hindsight and the marketing departments of brokerage houses.

Mr. Lesser Fool's assumption is based on selective hindsight and studies prepared by the marketing departments of brokerage houses.

Assorted academics, too lazy to dig deeper than the biased and non-representative stock indices, provide support for the Legend.

Since Mr. Lesser Fool expects to get a return on this investment by selling to Mr. Greater Fool, he understands that whatever he might think about the value of a stock, it is Mr. Greater Fool's opinion that matters.

Adopting The Crowd's Opinion

Mr. Lesser Fool's attitude towards stock value may be compared to the television shows during the 1990s in which people bring junk from their attics to traveling auctions to have it appraised by experts.

Here they are told that the old table that had been broken and chipped before being repaired would have been worth five thousand dollars, if they had just let it alone.

Now, painted and renewed, it is worth only five hundred dollars.

Mr. Lesser Fool follows the opinions of the crowd.

The expert appraiser patiently explains that people who buy and sell such junk put greater value on stuff that is old and ugly, than on something someone would want to have in their home.

And so it is in the stock market.

If one hundred thousand Greater Fools think that dividends are not important, preferring increased earnings, Mr. Lesser Fool must follow the crowd.

The stock market determines possible liquidating value for a few, not utility for the many.

Greater Fools' fondness for earnings, rather than dividends, increased steadily during the 1980s and 1990s, and stock that sold for ten times earnings in 1980, fetched fifty times earnings in 2000.

Mr. Lesser Fool will adapt his method of evaluating stock to that of the crowd and will never sense a shortage of equities.

Mr. Lesser Fool seeks capital gains, not dividends.

Whether he buys a stock for ten dollars and sells it for twenty, or whether he buys it for one hundred dollars and sells if for two hundred – he makes the same return.

Mr. Lesser Fool can claim that market value equals intrinsic value because intrinsic value is irrelevant to him.

Mr. Dividend

Another market player, Mr. Dividend, is different from Mr. Lesser Fool in that he does not expect to take any monetary benefit from Mr. Greater Fool, but only from the issuer of the stock in the form of periodic dividends.

Mr. Dividend looks to the issuer, rather than to Mr. Greater Fool.

Mr. Dividend pins his hopes on the issuer and on his right to receive dividends, if any are paid.

Mr. Dividend is a practical person, often self-taught – an independent thinker.

He is not a gambler, but has a small businessman's practical appreciation of risk.

The price of his stock may rise or fall, but Mr. Dividend is unconcerned, as long as dividends hold steady or increase.

Mr. Dividend's motto is,

'Hold the principal and clip the coupons.'

An earthy American folk-saying sums up Mr. Dividend's love of cash payback:

'Money talks, bullshit walks.'

Mr. Dividend is admittedly a figure from the past and a fuddy-duddy, but he sleeps well at night.

For many decades before the 1970s, most stock investors were of the Mr. Dividend species, except around the immediate vicinity of the stock exchange.

Today, only IRS auditors and politicians equate income with wealth.

The notion of a rentier class, popular one hundred years ago, is largely forgotten today.

Reading novels from the nineteenth century, we note that wealth was often defined as 'settled income.'

Today, people (except for IRS auditors and politicians) do not judge wealth as income, but rather as the value of assets owned.

Forbes magazine regularly publishes a list of rich people, classified not by investment income but by the market value of their assets.

Bill Gates is considered one of the richest men in the world based on his holdings of stock in Microsoft Corporation.

However, throughout the Great Bubble, Microsoft had a policy of not paying dividends.

In buying stock, Mr. Dividend will look to the current cash yield and make comparisons with current yields of alternate investments.

However, in a wild bull market, Mr. Dividend has periods of low self-esteem.

He sees Mr. Lesser Fool's family becoming wealthy, while he stands on the sidelines with seemingly meager returns.

By 2000, Mr. Dividend was rarely seen among stock investors.

At some point in a rising market, he may sell his stock and invest in bonds or real estate.

Because dividend yields were devastated in the final decades of the last century, Mr. Dividend was rarely seen among stock investors in the year 2000.

In ecological terms, he became an endangered species.

Mr. Control

Finally, we come to Mr. Control, the third of our major market personalities. Mr. Control's primary interest is to own enough stock of a company so he can tell the board what to do.

Mr. Control doesn't care about dividends and usually wouldn't think of selling his controlling shares to Mr. Greater Fool.

Mr. Control is able to use company assets for his own benefit.

Having control of a corporation gives him the ability to spend company assets for his own benefit, anytime he wants, without having to go through the tax hassle of paying dividends or taking capital gains.

For example, Mr. Control can travel around the world first-class, eat at the best restaurants, and stay at five-star hotels – all paid for by the company.

If the company is big enough, he can have a private jet and a five thousand square foot office, with adjoining squash court, swimming pool, and a private, catered dining room.

He can have an army of private assistants to remind him of birthdays of family and friends, make appointments, run errands, fix his fleet of company-owned Mercedes, keep his books and calculate his income tax.

He can guarantee employment for his wife, children, distant relatives, and cronies.

He can give company money to universities and hospitals in exchange for his name on a building, honorary degrees, and good citizen awards.

He can rub shoulders with famous people and be called on by presidents and ministers to whose personal finances he directs company funds, living a life of unending ego-gratification.

However, Mr. Control is not necessarily any more of an amoral, selfish capitalist, than Mr. Dividend or Mr. Lesser Fool.

He may seek to control a company to develop lower-cost steel or find a cure for cancer.

It takes luck or money to be Mr. Control.

Mr. Control may want power to benefit others or to put his own ideas into motion.

It takes luck or money to be Mr. Control.

Often Mr. Control comes by his dominant interest in a company by marriage or inheritance and would not think of selling stock.

Sometimes Mr. Control saves money, gets backers, and creates the enterprise that he owns.

Otherwise, Mr. Control must get power by tactics that rely more on the art of war and Machiavellian politics than investment theory.

In large public companies, control may depend on ownership of a small percentage of the capital stock, combined with tactics to soothe and hoodwink other investors.

As described in the Essay on 'The Great Misleading', a professional manager can use buybacks to boost market prices and win over Lesser Fools and their advisers, keeping control of a public company for personal benefit.

The Value of Control

Mr. Control's concept of value is not abstract or theoretical.

Like Mr. Dividend, he expects to get the return on his investment from the company, but he expects much more than his fair share.

Therefore, he values a company more highly than justified by the future stream of dividends.

Mr. Control expects much more than his fair share.

Imagine that Mr. Control owns forty-nine percent of a company and ten thousand people like Mr. Lesser Fool own the other fifty-one percent, held indirectly through various mutual funds.

The company's only asset is one billion dollars in cash.

The book value of one percent of equity is ten million dollars.

Say also that without fifty-one percent of the company, Mr. Control cannot make the company do as he wishes, because fund managers have elected their representatives to the board.

Therefore, Mr. Control considers how to buy two percent of the equity from fund managers.

How much should he pay?

Clearly, two percent is worth more than twenty million dollars in book value, since it would give control of one billion dollars and the special 'dividends' associated with control.

He may seek someone from whom to buy two percent for, say, forty million or even one hundred million dollars.

The value of controlling shares is greater to the acquirer than to other investors.

Even if Mr. Control accepts many of Mr. Dividend's ideas about fundamental value and does not intend to use the company as a personal piggy bank, he will pay more for a controlling interest because he figures that control lessens investment risk.

The value of a controlling interest depends on the firm's financial condition, the breakdown of shareholders, the acquirer's current position and access to credit, and the possibility of swapping overvalued stock for shares of the target company.

There is no simple way to value controlling shares and the choice is subjective.

There are many like Mr. Control roaming the market, seeking to dominate the assets of this or that company.

Controlling shares are worth more to the acquirer than to other investors.

Control can often be held with only a fraction of the stock of a company.

The price that an acquirer is willing to pay distorts stock values for ordinary investors, since a controlling interest is more valuable than a stocks worth to a minority holder.

This disappoints Mr. Dividend, but pleases Mr. Lesser Fool, who seeks capital gains and a chance to ride with Mr. Control for a short-term speculative profit.

Wall Street Dislikes Mr. Dividend

It would be better for the country to have no taxation of dividends and capital gains.

This would remove the fiscal distortion that increases risk in capital markets.

However, the conflicted interests of Wall Street, causes investment bankers to fight far harder to remove capital gains taxes than taxes on dividends.

Financial intermediaries earn greater commissions from active traders than from long term investors.

Financial intermediaries earn greater commissions from active traders than from long term investors.

An investor like Mr. Dividend, who chooses stocks to hold for the long-run, is not the favorite client of stockbrokers.

Instead, brokers love Mr. Lesser Fool who seeks to pile up capital gains by day trading.

They also like Mr. Control because of the prospects for fat fees in managing mergers, acquisitions, and takeovers, as well as arbitrage and speculative profits.

Wall Street has repeatedly come to Congress to contend that unless capital gains taxes are revoked, American Industry will not be able to raise funds that create jobs for workers.

This argument ignores the fact that since the 1980s, American corporations bought back and retired more stock than they issued.

Most new capital raised went overseas to create jobs for foreigners.

If Wall Street was really interested in creating jobs, they would argue for eliminating the tax on dividends and ask for tax incentives for new issues, measures that might build an equity base to sustain long-term, steady employment.

Capital gains taxation is a levy on speculation, while dividend taxes harm long-term investors and retirees.

The tax differential between debt and dividends encourages speculative capital structures and endangers economic stability.

The Anti-Dividend Lobby

President Bush, in 2003, like President Reagan twenty years before, proposed that double taxation on dividends be abolished, but support from Wall Street was lukewarm and most professional executives – beneficiaries of fraudulent stock buyback schemes – opposed the idea, as they had under President Reagan.

Double taxation of dividends encourages leverage, with greater societal risk.

Politicians from the Democrat Party, true to their demagogic roots, claimed that abolishing taxes on dividends would only benefit the rich, forgetting the tens of millions of Americans that were dependent on dividends for retirement income.

Proponents of ending double taxation on dividends failed to advance the substantive argument that the long-term fiscal bias against dividends encouraged highly leveraged capital structures, with increased societal risk.

Funds Prefer Capital Gains

Fund managers prefer capital gains to dividends.

Tax laws require that mutual funds distribute income from cash dividends each year, whereas capital gains must be distributed, only if realized.

Capital gains must be distributed by fund managers only if realized.

If stocks were priced as a multiple of bond yields, values would be much lower and fund managers would have to distribute a greater percent of assets to investors each year, and this would reduce their management fees.

In fact, if traditional dividend-based stock values had persisted, by the millennium fund managers would have received only about one-quarter the fees they actually earned.

Basing stock prices on bond yields limits inflation of portfolio values and consequently limits portfolio management fees.

Fund managers are rewarded for money that stays in the fund, not for the dividends paid to stockholders.

Investors, who for half a century trusted fund managers to vote in their interests, have been deceived.

Changing Players and Perceptions

The players in the equity market in the 1990s were not like those of the 1920s. In 1929, equity prices were high – about twenty times earnings – but this was one-third less than the heights reached in 2000.

By 2000, dividends had fallen to only twenty percent of bond yields.

Dividend yields in 1929 were similar to yields on investment grade bonds, whereas by 2000, dividends had fallen to only twenty percent of bond yields.

Before the 1990s, the stock market varied between price earnings ratios of ten, in bear markets, and twenty, in bull markets.

Until the 1970s, most stocks had dividend yields that were higher than bond yields.

In 1929, price-earnings ratios had reached the normal high in bull markets and many investors had the common sense to sell before the Great Crash.

No More Like Charles Merrill

In 1929, stockbrokers were partnerships and partners had unlimited personal liability.

Charles Merrill, the founder of Merrill Lynch, took the principled step of warning clients that prices were too high.

He even tried to convince President Coolidge to do something to stem speculation.

Charles Merrill was right; Irving Fisher was wrong.

Merrill sold his own portfolio before the October 1929 crash, as did speculators like Joe Kennedy, the father of JFK.

While Charles Merrill was trying to warn clients that stocks were too expensive, America's most illustrious economist, Professor Irving Fisher of Yale University, was proclaiming that stocks were under-valued, even in the week of the Great Crash.

Fisher was a founder of the Econometric Society and had published many works using mathematics to expound financial economic theory.

He stuck stubbornly to the belief that stocks would rise higher than the peaks of 1929.

Fisher lost his fortune and lived his final years with an impaired reputation, permitted to stay in his campus home thanks to charity of Yale University that took over the mortgage.

The fall in stock values did not cause the Great Depression – only a small percentage of Americans owned stock.

Poor banking practices were to blame. Bank deposits were uninsured and Washington did a dismal job of overseeing bank loan portfolios.

After the market crash, commercial and investment banking were separated, bank deposits were insured, and a Securities and Exchange Commission regulated stockbrokers.

'Rational Thinking' in 2000

In any speculative market, Mr. Lesser Fool is king, and the Great Bubble of the 1990s was no exception.

By 2000, the lessons of 1929 had been forgotten.

The lessons of 1929 were forgotten. Some economists had learned nothing in seventy years.

Economists at the Federal Reserve proclaimed that 'Irving Fisher Was Right!' and that stocks, indeed, had been under-priced in 1929:

'The Stock Market Crash of 1929: Irving Fisher Was Right!', Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Staff Report 294, Ellen R. McGrattan and Edward C. Prescott

The Glass-Steagall Act separating investment and commercial banking had been revoked.

Banks were again lending on a grand scale with stock as collateral, but not so much through margin accounts as through hidden side deals to giant corporations like Enron and WorldCom.

Stockbrokers had incorporated their partnerships and Wall Street executives had contrived to limit personal liability.

The SEC and Federal Reserve developed a cozy, revolving-door relationship with broker-dealers, law firms, and accountants.

Unlike 1929, top executives of Merrill Lynch in 2000 did not advise clients to sell stock.

Nor did they try to convince President Clinton to stem stock speculation.

A Different Merrill Lynch

Few professionals thought stocks were overvalued at thirty or forty times earning during the Great Bubble.

The investment judgment of David Komansky was exposed to public view.

In 1998, the investment judgment of David Komansky, the chairman of Merrill Lynch, was exposed to public view when the Federal Reserve engineered the bailout of Long Term Capital Management.

LTCM was a hedge fund run by the arbitrageur and gambler of Liar's Poker fame, John Meriwether – the trader who had left Salomon Brothers after a scandal involving lying to the government about the purchase of U.S. Treasury bonds.

Chairman Komansky had invested substantial amounts of his own money in this venture, and Merrill Lynch, his company, was later to invest a further three hundred million dollars as part of the bailout package.

LTCM had gotten into trouble by leveraging investor's capital over forty times to purchase a portfolio of two hundred billion dollars in derivative securities, with contracts of over one trillion dollars in notional value.

Even worse, LTCM provided almost no information to its shareholders.

When we compare the personal investment behavior of the founder, Charles Merrill, in 1928, with that of the professional manager, David Komansky, who ran this company seventy years later, we see why many were confused in the Great Bubble of the 1990s.

(See Essay: 'Uncontrollable Risk')

Mr. Dividend Is Outnumbered

By the year 2000, Mr. Dividend's people were pariahs and were outnumbered by Mr. Lesser Fool's gang.

Millions of ordinary investors, instead of relying on commonsense, now depended on the wisdom of professionals and experts who were biased and weighed down by conflicts of interest.

In 2000, ordinary investors depended on biased and conflicted professionals and experts.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission licensed intermediaries and administered rules that were designed to protect investors in the 1920s.

University professors assured the masses that, in the long-run, 'economic science' proved that stocks were the best investment.

In retrospect, the normal bull market peak of twenty times earnings had been reached by 1995.

One might have expected a normal reaction to set in, if markets were cyclical.

However, the institutions had changed and few noticed.

- Issuers, instead of rushing to sell equities and take advantage of low capital costs, stepped up their multi-billion dollar buyback and stock option schemes.

- No longer did stockbrokers have unlimited personal liability and stocks of brokerage houses were traded on the exchange.

- Any broker that advised clients to get out of the stock market would be acting against the interests of his company and would be fired.

Investors erred by trusting these conflicted Wall Street professionals, delivering their life savings to mutual funds to invest in stocks, ignorant of the long-term merit of the securities they were buying.

Academics Support the Bubble

Investors switched from commonsense dividend-based pricing to the ideals of Mr. Lesser Fool.

There was general acceptance of fantastic theories of Nobel laureate economists.

The players in the capital market were irrational and ignorant of their own best interests – except, of course, for the intermediaries, fiduciaries, and economic quacks that had the cunning and coolness of mind to take advantage of the ignorance of the common investor.

To be fair, most market intermediaries themselves believed the Common Stock Legend.

By 1999, senior Wall Street executives had spent entire careers in a perpetual summer of rising stock prices.

By the mid-1980s, Wall Street was packed with MBAs from Harvard, Stanford, and other prestigious universities.

As part of their education, they learned academic versions of the Common Stock Legend and were pledged to the fraternity of the Efficient Market.

By 1999, many senior Wall Street executives had spent entire careers in a perpetual summer of rising stock prices.

Temporary blips like the Crash of October 1987 only served to confirm the Common Stock Legend.

The interplay between Mr. Dividend, Mr. Lesser Fool, and Mr. Control, overseen by conflicted Wall Street interests, illustrates the Irrationality Axiom of Capital Flow Analysis.

Mass marketing of mutual funds to over sixty million trusting investors during the last half of the twentieth century, helped along by a sleepy and friendly Securities and Exchange Commission, raised an army of Lesser Fools that fought the battle of the Great Bubble in the Clinton years.